How Hasbro Found Robots and Created a Universe

From Tokyo to Pawtucket and on to New York

In June 1983 Hasbro’s scouts encountered Takara’s transforming toy lines at the Tokyo Toy Show; Hasbro licensed and rebranded these toys for the North American market as The Transformers. To sell them as something beyond a simple gimmick, Hasbro commissioned a backstory and constructed a multi-media launch — a Marvel Comics series and a syndicated cartoon, coordinating toy design, naming, and tie-in content across teams mostly based in Tokyo, Pawtucket (Rhode Island) and New York City.

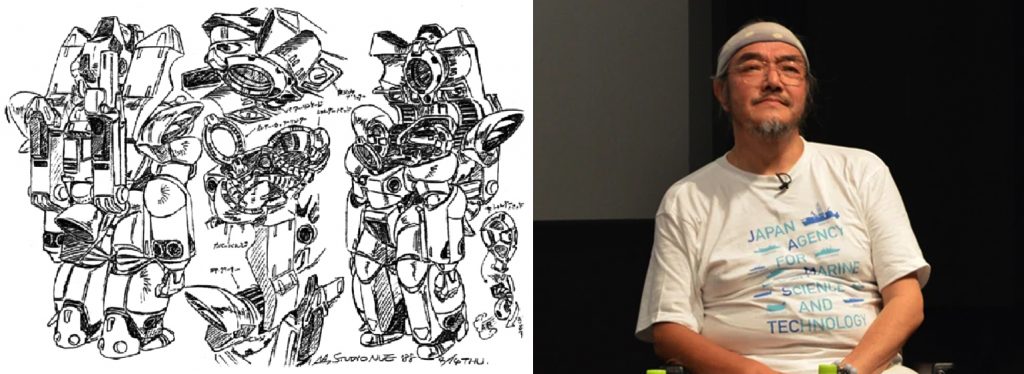

The discovery itself is now a well known brand origin story: Hasbro representatives attending the Tokyo Toy Show saw Takara’s Diaclone and Microman/Micro Change toy lines — compact, mechanically clever robot toys that transformed into vehicles or weapons — and recognized an opportunity to import and rebrand them for western markets. Contemporary accounts and later company histories say Hasbro sent at least one representative to the show and quickly moved to license both moulds and concepts. That deal set a technical foundation moving forwards: the toys (moulds and mechanical engineering) came from Japanese firms led by designers such as Shōji Kawamori and Kazutaka Miyatake (Studio Nue), who had worked on Diaclone-era mecha designs in Japan.

Hasbro’s corporate base was, and is, in Pawtucket, Rhode Island; from there Hasbro’s product and marketing teams coordinated the U.S. launch (packaging, names, advertising and distribution). Hasbro’s decision making was strategic: instead of launching several separate Japanese lines with different names, they consolidated the toys under a single, unified brand and a single (sort of), strong story to avoid consumer confusion and to enable broader merchandising. This consolidation drove the fast and ambitious cross-media program that followed.

From moulds to myth: who created the characters and the story? New York writers and Tokyo designers

Once Hasbro had the toys, the next problem was identity: what are these characters called? Why do they exist? How do they hang together as a line? For that Hasbro turned to collaborators who could deliver a sellable mythos and tie-in media.

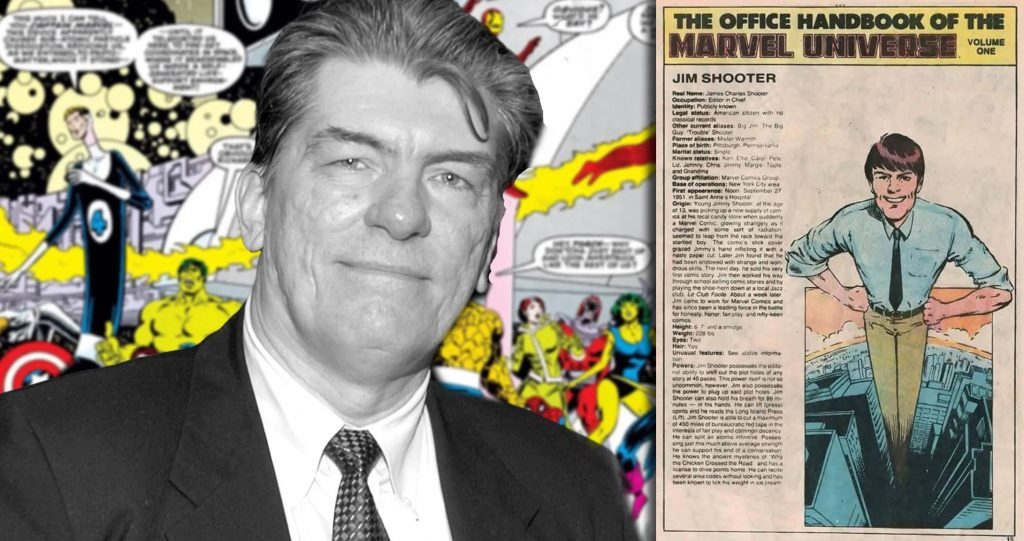

Jim Shooter, editor-in-chief at Marvel Comics in New York, drafted the original series treatment that set the core premise: sentient robots from a planet called Cybertron, two factions (Autobots and Decepticons), and a crash landing/arrival on Earth that would give a strong setting to map to story. Shooter’s early treatment established key structural elements — factions, terminology (the names “Autobot” and “Decepticon” are credited to that development plan) and set in place the overall war-on-Earth beat used in both the cartoon and the comic. Shooter’s retrospective writings and interviews confirm his central role early in development.

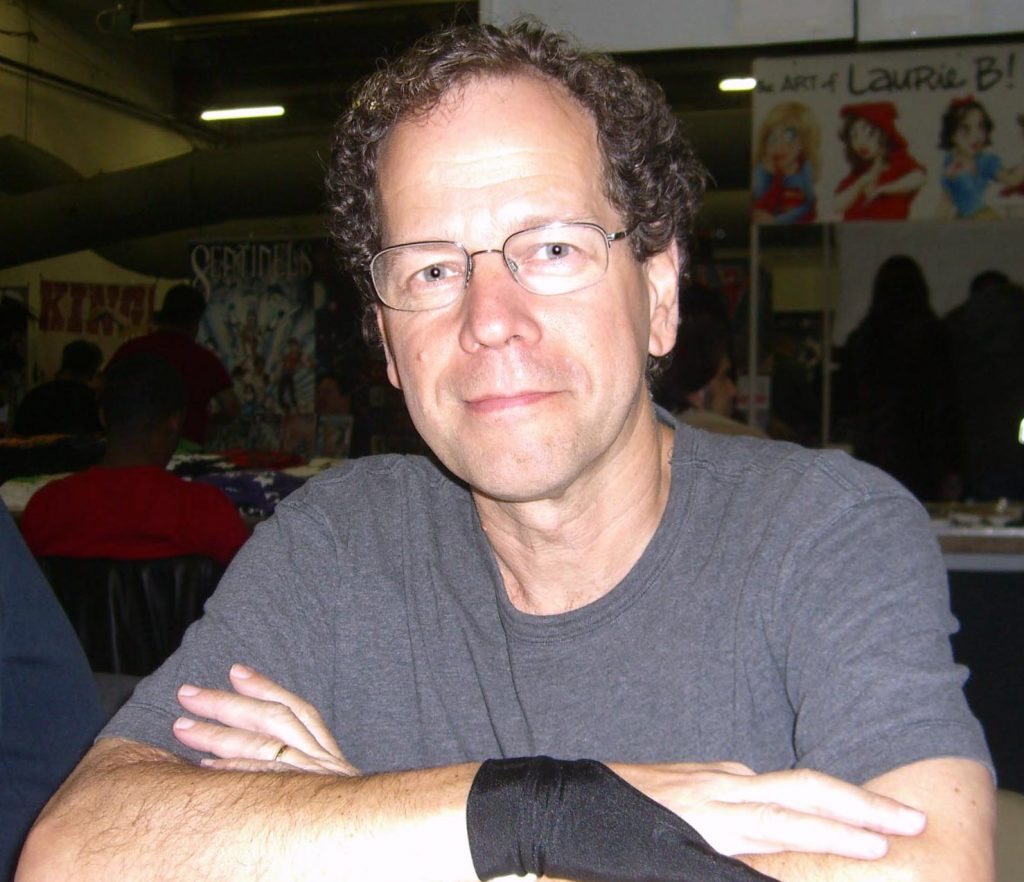

With the treatment in hand, Marvel’s editorial team and writers fleshed out names, personalities, and short biographies for individual toys. Bob Budiansky, a Marvel editor and writer working in New York, wrote many of the character names and the bite-sized “bios” that appeared on cards and in promotional materials; Budiansky later wrote many of the early issues of the Marvel Transformers comic. He has repeatedly described being tasked to provide hundreds of names and profiles and to help make the toys feel playable as characters with personalities — a crucial step that converted plastic moulds into characters kids could care about. The names and profiles that helped market “the plastic” we love were almost entirely a product of Marvel’s editorial team. Although many others were involved, Shooter’s treatment and Budiansky’s character development see them both credited as the main creators of the mythos and franchise we celebrate today.

The toy design side remained largely Takara’s domain. Designers Shōji Kawamori and Kazutaka Miyatake from the Diaclone/Microman continued to conceive more toys in Japan. Takara’s design choices (transformation mechanics, combining units, ideas that played with scale) were what really made the toys special. After licensing them, Hasbro largely kept the engineering and moulds unchanged, adapting packaging, making some colour changes and inserting the Marvel-supplied names and bios. Contemporary accounts and the Diaclone archive also credit Kawamori and Miyatake with direct design contributions that fed into the G1 Transformers line.

Turning toys into a TV show: Sunbow, Marvel Productions, Toei, AKOM, and Nelson Shin

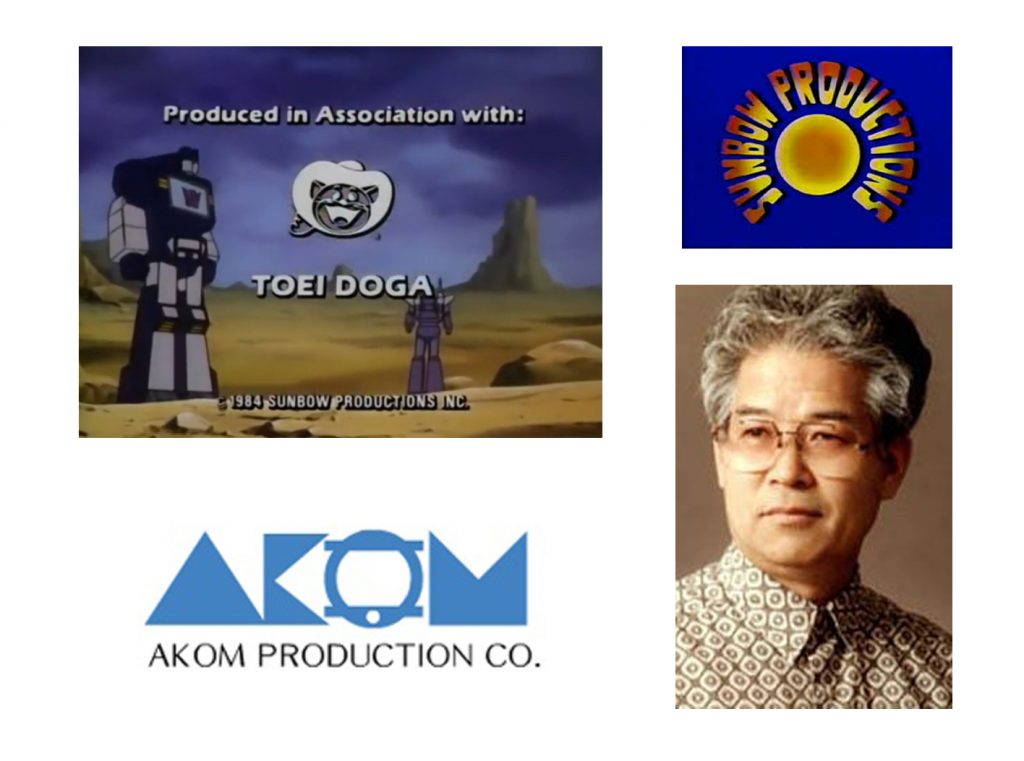

Hasbro wanted as much shelf presence as they could get for this new line — they wanted mass-market reach for their new narrative. They decided to use television, planning an animated series to accompany synchronised toy waves and a complimentary Marvel comic. The series was produced in the U.S. by Sunbow Productions (an advertising/animation producer founded by the Griffin-Bacal agency) in partnership with Marvel Productions. Sunbow was originally formed precisely to create marketing-driven cartoons for toy clients, as it had already successfully done with G.I. Joe for Hasbro. Executive producers in the U.S. (names associated with early production include Joe Bacal, Margaret Loesch, and Tom Griffin) oversaw the project and coordinated scripts, music and the production pipeline.

Because television animation was expensive in the U.S., most of the actual frame-by-frame animation was farmed out to overseas studios. For Transformers that meant Toei Animation in Tokyo handled large chunks of early animation (season 1 and parts of season 2), and AKOM in Seoul (South Korea) did a lot of the later seasons’ work (and the feature film animation) under Nelson Shin’s direction and production supervision. Nelson Shin, a Korean-born animation director who had worked in the U.S. and helped found AKOM in Seoul, served as the TV series producer and later directed The Transformers: The Movie (1986). The production chain therefore spanned New York (story, voice recording, production oversight), Tokyo (Toei animation), and Seoul (AKOM animation production).

When it came to writing the televised episodes, the show employed a mix of U.S. television writers and story editors. Early staff and freelancers (names who appear in episode credits and production documents) included people like Bryce Malek, Dick Robbins, Jeffrey Scott, Flint Dille, David Wise, as well as others who wrote or edited TV scripts in Los Angeles and New York production contexts. Marvel’s initial treatment was used as the backbone, but Sunbow and Marvel Productions developed episode outlines and scripts suited to daily syndicated television. The U.S. writing teams’ job was to adapt toy play patterns into 22-minute stories that showcased the characters, promoted new toys, and adhered to the day’s broadcast standards, more on that later!

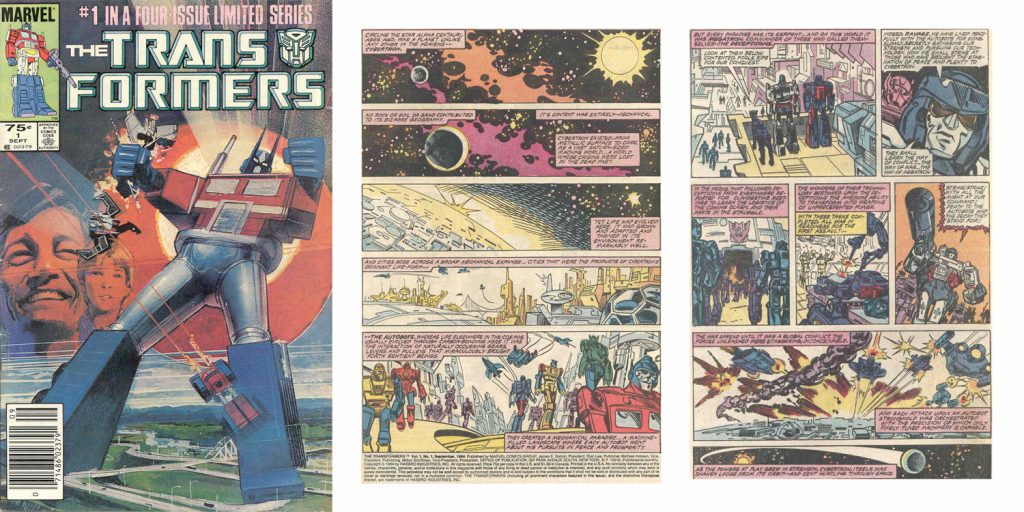

The comics: parallel continuity, creative freedom, and different tones

Hasbro intentionally launched the toys with multiple, coordinated media pillars: TV and comics. Marvel Comics produced a monthly Transformers comic that also began in 1984; it was originally planned as a limited series but expanded into an ongoing 80-issue run (1984–1991). Marvel used Jim Shooter’s treatment as the structural backbone, and Bob Budiansky and other Marvel writers (including later Simon Furman in the UK) wrote long-running continuities that somewhat diverged from the cartoon. The comic allowed longer, meatier storytelling and a notably different tone (grittier, sometimes darker) — providing supplementary origin material and character development for a mainly older readership. The comics therefore functioned as both tie-in and creative outlet, often influencing the toys and vice versa – for example, some characters debuted in the comic before appearing on screen or in toy waves.

Why 1983–1984 matters: timing, toy culture and the regulatory context of the day

Two industry factors made the rapid Transformation (ha!) of the 1983–1984. U.S. toy market possible. Firstly, by the early 1980s Japanese toy engineering technology had produced the necessary transforming interlocking toys in the Diaclone, Microman and Car-Robots lines. Obviously, without toys that were mechanically interesting and robust enough for mass production, the U.S. retail market could never have presented our favourite brand under any guise. Secondly though, regulatory changes and broadcast economics in the U.S. made it viable and legal to create syndicated cartoons that were effectively long commercials for toys (a strategy Hasbro also used successfully with G.I. Joe).

The Reagan administration had pursued a broad policy of deregulation that significantly reshaped American media and consumer culture, particularly in the realm of children’s advertising. One key move was the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) rollback of rules that had previously limited the blending of entertainment and advertising. In the late 1970s, guidelines restricted the amount and nature of children’s commercials. This prohibited programming that functioned primarily as toy advertisement. By 1981, under Reagan’s appointee FCC Chairman Mark Fowler, those restrictions were eased or abandoned altogether. The FCC shifted its philosophy away from regulation in the “public interest” and toward a market-driven approach, arguing that parents and the free market were best suited to decide what children consumed. It was this change that cleared the way for these “program-length commercials” — shows built entirely around toys.

Hasbro’s swift decision to unify multiple Japanese toy lines under one brand, and to take advantage of this cultural and regulatory window, brought immediate results, explosive sales and left a huge cultural footprint. Fortunately timed regulatory rollback ultimately Transformed (and again!) Saturday morning television and with it our childhoods.