Transformers: The Story of 1985 - 1987

The public response to what we now know as G1

As a young child with a love of robots and futuristic action, Transformers really spoke to me. Back then, I had no concept of how toys were made or who invented them. It’s only now, as a greying adult, that I find myself curious about what was happening behind the scenes. In my last article I tried to explain why there were any transforming robots on Western toy shelves at all. Perhaps one day I’ll take a deeper look into why the Japanese were making them in the first place. In future pieces I’d like to explore more about the genesis of the characters and writing behind my favourite cartoon, but for now I’m tracing the broader arc of the G1 era of the franchise.

When Transformers hit the U.S. market in late 1984, the public response was immediate and positive — especially among children and toy collectors. Hasbro’s decision to unify Takara’s transforming toys under a single brand, combined with a syndicated animated series and Marvel-created character identities (names, bios), turned what might have been a niche import into a mass-market phenomenon. Retailers reported more than brisk sales during the 1984 holiday season and on into 1985; according to fan-compiled retail aggregates, 1985 became the line’s biggest commercial year, with contemporary industry commentary revealing explosive demand for the toys. Hasbro’s marketing and distribution apparatus, centred in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, had successfully converted Japanese mechanical ingenuity into a massive American hit.

The TV show — produced in the U.S. by Sunbow Productions and Marvel Productions (New York/Los Angeles production nexus) — functioned as the public face of the line. The cartoon’s early episodes focused on introducing characters and play patterns; each episode effectively an extended advertisment for multiple toy figures. Critics of children’s television later described the series as emblematic of the deregulated 1980s advertising environment that allowed programming to be so closely tied to merchandising. The series’ animation (largely produced overseas) and its theme song became part of a cultural imprint that went beyond the toys: kids’ clubs, schoolyard play, and extensive coverage in toy magazines turned Transformers into one of the decade’s signature children’s properties.

Internationally the toys and show were received strongly as well. While the U.S. was the largest market, the combination of visually arresting designs and an easily localisable TV format meant that Transformers took off in markets as diverse as the UK, Canada, Australia as well as parts of Europe and Latin America. Translation and localised broadcast schedules meant kids around the world were introduced to the Autobot/Decepticon conflict, increasing toy demand across markets and prompting Hasbro (and Takara) to coordinate regional waves of releases.

Expansion - always more toys and the establishing of the continuities

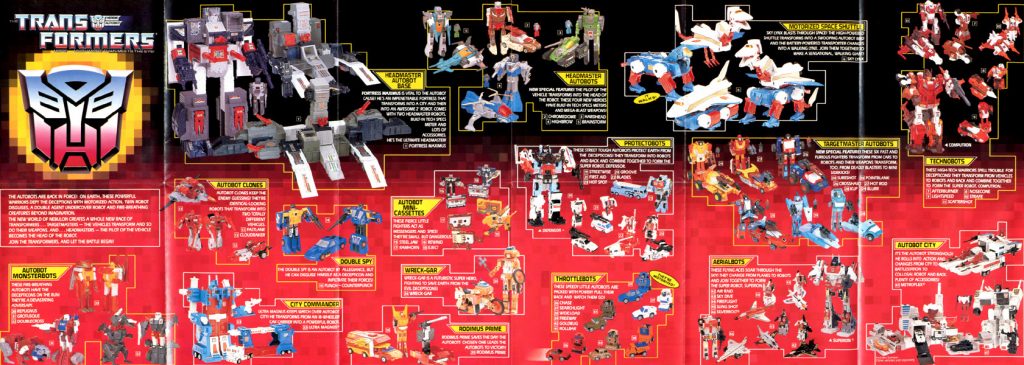

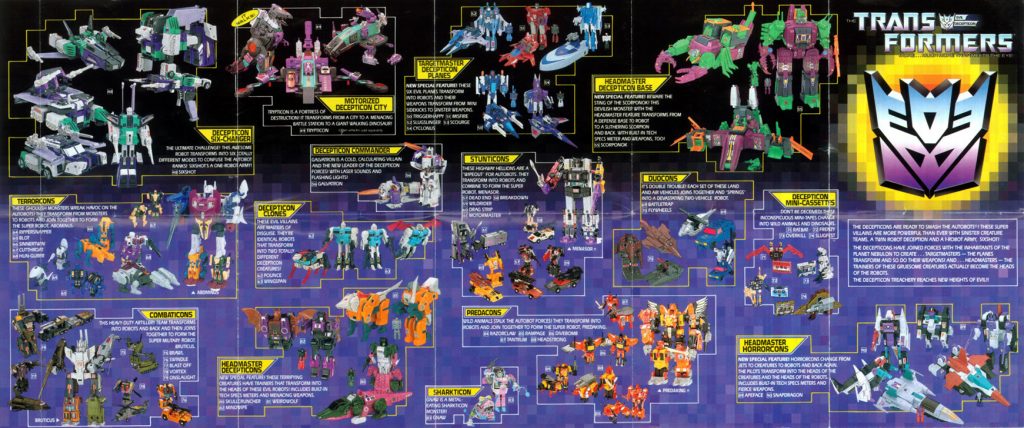

In 1985 the franchise broadened significantly. Hasbro introduced new Autobots and Decepticons, including some different flavoured characters such as Omega Supreme, Jetfire, Cosmos and the Insecticons. The new wave of toys also introduced “combiners” (teams that formed larger robots), these additional subteams (Aerialbots, Protectobots, Stunticons, Combaticons) saw Hasbro to constantly shipping new SKUs into stores. Integrating these figures into the storyline marked a major expansion to the original lineup, deepening the world’s mythology.

The TV series expanded its roster of episodic writers — US-based writers working under Sunbow/Marvel Productions — adding more serialised stories, multi-episode arcs, and complex toy-driven plot devices that showcased new releases. The Marvel comic (New York City editorial base) continued to run in parallel, expanding lore and often diverging from the show’s continuity. The comic’s more adult-leaning and ongoing serialised storytelling complemented the cartoon’s 22-minute, toy-focused format and helped keep older fans engaged as readers.

1985 is also the year the franchise’s true commercial size became clear. The toy business was hitting a peak: sales data compiled by collectors and industry observers place 1985 as an especially successful year for all Transformers merchandise; a combination of massive holiday sales, wide store shelf placement, and the cartoon’s saturation of the airwaves contributed. This market success reinforced Hasbro’s approach: new characters in the toyline would now almost always be backed by a TV appearance and/or comic presence in order to maximise cross-media visibility.

In the UK and the US, Christmas 1984 had seen children’s wish lists dominated by Transformers and GoBots, He-Man and the Masters of the Universe figures, and the ever-popular Cabbage Patch Kids. Other coveted toys of the season included G.I. Joe action figures, My Little Pony, and a range of Kenner favourites such as Care Bears and Super Powers Action Figures. By Christmas 1985, the must-haves had evolved to include the groundbreaking animatronic Teddy Ruxpin. Pound Puppies, Cabbage Patch Kids, and home video game consoles like the Atari were also in high demand. For the second year running, Transformers remained one of the most sought-after toys of the season—its popularity supercharged by the now-ubiquitous cartoon series capturing imaginations across the world. Transforming robots were a legitimate phenomenon, outperforming all expectation.

1985’s Season 2 is often seen as the joyful peak of the cartoon by G1 fans, containing many of the most memorable episodes and the widest range of characters.

1986 — The Movie - a creative gamble - consumer backlash

1986 was a watershed. Hasbro and their production partners aimed to reset the toy lineup and clear inventory by using a dramatic narrative device — the death of high-profile characters — in a full release feature film. The Transformers: The Movie was co-produced and directed in animation terms by Nelson Shin, tied to producer/animation house AKOM as well as the US production team. It premiered in North America on August 8, 1986. The movie’s producers and writers (US-based script and story teams working with overseas animation studios) intentionally killed several major characters — most notably Optimus Prime — to make way for new toys in an attempt to signal a generational shift in the product line. The film also sought to widen the story universe (introducing Galvatron, Unicron and the Quintessons) with higher-stakes storytelling than the weekly TV series had allowed.

Hasbro introduced a host of new characters from the film, including Rodimus Prime, Ultra Magnus, Galvatron, Kup, Hot Rod, Springer, Arcee, and the massive planet-eater Unicron, though the latter infamously never saw a full retail release at the time. The Junkions also joined the mythos, reflecting the film’s wider galactic scope beyond the traditional Autobot–Decepticon conflict. The new figures featured more complex transformations and vivid metallic colour schemes that set them apart from earlier waves. Together, the 1986 line cemented Transformers as a vast, evolving universe—one that merged cinematic spectacle with cutting-edge toy design.

And then…

The backlash to the movie, in particular the death of Optimus Prime, was swift and very visible. In the US, children’s emotional reactions translated into a letter-writing campaign to Hasbro and public outrage among fans and parents. Wrtitten about in newspapers and seen on TV news, the outcry made two things clear: 1) viewers (especially children) had formed deep attachments to specific characters, and 2) the abrupt narrative deaths could threaten both the show’s brand equity and retail demand. As a result of the public response, Hasbro and the TV producers acted almost immediately: the TV show would later revive Optimus in a two-part season finale in early 1987, a decision wholly made under clear commercial and PR pressure. The movie did succeed in refreshing the brand and clearing older moulds, but it also taught the franchise a lesson about balancing narrative risk with merchandising realities.

Artistically and technically, the movie marked another turn: Nelson Shin — who had been heavily involved in the television project and who established AKOM in Seoul — and overseas houses (Toei in Tokyo also animated much of the TV series) became more visibly integrated with U.S. production intentions. The film’s animation and soundtrack choices (including the high-energy opening song and rock-oriented score) signaled an effort to position Transformers as a more cinematic property. The film’s release also coincided with evolving broadcast tastes and a crowded children’s programming marketplace.

Critical Reaction

Critics were mixed. Some praised the film’s ambitious visuals, the scale of its action sequences, its comparatively mature tone, and the boldness of its storytelling choices — particularly the decision to kill off beloved characters. On the flip side, many critics saw the film as little more than a glorified toy commercial, some criticising its violence, tonal inconsistency, and jumbled storytelling.

Technically, though, the movie was a definite step up for the franchise. Animation quality, especially in battle scenes, saw a significant increase in quality, a particular highlight being the depiction of planet sized Unicron – unthinkable detail when compared to Season 1. The soundtrack, heavy with 80s rock and futuristic synth sounds, was beloved at the time, instantly becoming iconic. The voice cast was recognised: big names like Orson Welles (Unicron), Leonard Nimoy, Judd Nelson, plus regulars like Peter Cullen, gave gravitas. Critics noted that the movie definitely seemed more visually polished than the standard TV episodes. However, the technical merit did not fully compensate for the criticisms: narrative confusion, pacing problems, and the severity of character deaths left some non-fan viewers cold.

Over time, as we know, the fan community has reappraised the film somewhat: it’s achieved cult status. Many now regard it fondly as a classic, valuing its ambition, emotional weight, soundtrack, and its role in shaping the Transformers mythos. At the time fans response was more emotionally charged. Appreciated for being daring: the new characters, large stakes and genuine losses gave a darker, more epic tone than the weekly cartoon. Optimus Prime’s death is often cited as one of the most memorable, upsetting, and defining moments in Transformers lore, with some fans feeling betrayed by the apparent killing off of characters they had grown up with, especially since those deaths seemed so permanent in the film’s narrative. There was also criticism that some of the new characters seemed as if they were introduced for toy sales rather than for enriching the story.

Box Office & Commercial Outcome

On paper, the film was a commercial disappointment. It had a budget of about US $5-6 million and grossed around US $5.8 million in the US & Canada. So it failed to make much profit theatrically. International performance was also modest.

This poor box office is often attributed to several factors: the film’s release amid heavy competition in the summer of 1986 – a crazy year for cinema seeing the release of Top Gun, Aliens, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Stand by Me, The Karate Kid Part II, Blue Velvet, The Fly, Flight of the naviogator, Labyrinth, Big Trouble in Little China, Howard the Duck and many other films considered very watchable classics to this day. Although all these films were not direct competitors, the sheer quality of Hollywoods output lead to very high expectations at the time.

Some believe Transformers: The Movie’s darker, more violent tone alienated part of its younger audience. Mixed critics reviews likely limited its appeal beyond existing fans. As for toy sales: while there is less hard data publicly available correlating immediate toy earnings to the backlash, there are signs that Hasbro paid a price. Analysts at the time reportedly suggested that Transformers toy sales dropped after the movie when compared to the earlier peak years, so arguably it did hurt the toylines’ momentum.

1987 — the last G1 episodes - shifting strategies - international divergence

By 1987 the U.S. syndicated television landscape and the toy market were both changing. Hasbro continued to ship toys and to support the brand, but the company and its production partners were adjusting to: declining novelty for the initial G1 molds, the need to develop new toy concepts, and shifting audience attention across children’s programming. The television series produced the three-part “Rebirth” (airing November 1987) after the two-part return-of-Optimus arc earlier in the year. These episodes are generally treated as the end of the original US G1 broadcast run (the last widely acknowledged G1 story episodes airing in 1987).

The tone of the 3rd and 4th Seasons are seen as sombre and less madcap, although they definitely have their wackier moments. The change of leadership to the often maligned Rodimus Prime did not sit well with all fans, many commenting that his lack of will to lead was draining to watch. Having said this, a large number of fans find the episodes proceeding the 1986 film to be the best and most watchable as an adult fan. In the same way as the film is seen in a much more favourable light nowadays, the final seasons have drawn much praise in recent years.

After this point Hasbro and Takara’s strategies diverged: while Hasbro moved into subsequent toylines and refreshes for Western markets, Japanese partners and broadcasters produced new animated material that continued the story in locally produced continuations (Headmasters and other Japan-only series), reflecting local tastes and licensing relationships. In short: 1987 marks the end of the US broadcast era of the original G1 continuity, whilst Japan carried on with its own sequels.

Staff changes — writers, producers and animation houses

One of the distinctive features of the G1 era was how international and changeable the production pipeline was. The earliest seasons leaned heavily on Japanese animation studio Toei (Tokyo) for large portions of animation, with US production offices (Sunbow/Marvel Productions in New York/Los Angeles) providing scripts, voice recording and direction. As the series moved forward, a mix of studios and producers rotated through the production: AKOM (Seoul), founded by Nelson Shin, became increasingly important for both the TV series and the feature film animation work. The result was a changing “look” and sometimes uneven animation quality across seasons. This did not go unnoticed by critics and fans. Production credits make this clear: early episodes credit Toei heavily, whereas later seasons and the movie credit AKOM and other Korean houses more prominently.

On the writing side, the show’s early identity came from Marvel’s initial treatment and the cadre of American TV writers who adapted toys into episodic stories. Over the run, story-editing duties changed hands: later seasons see names like Flint Dille, Marv Wolfman, Steve Gerber and others involved in story editing and shaping larger arcs. These shifts reflected both creative adjustments (the need for longer arcs and continuity after the movie) and the changing expectations of syndicated TV — scripts increasingly had to juggle story, toy-promotion beats, and the fallout from fan expectations (e.g., the effort to bring Optimus Prime back). As story editors and writers rotated, the show’s tone evolved from simple product-demonstrative episodes to more serialised and sometimes darker or more complex stories, particularly in the seasons that followed the film.

Voice talents and production personnel were also affected: the voice actors were US-based (recording typically in New York or Los Angeles), but animation direction and overseas production were increasingly coordinated by producers operating out of Seoul (AKOM) and Tokyo (Toei) — a production geography that underscored the G1 franchise’s international nature. The combination of changing animation houses and new story editors produced episodes that looked and read differently across seasons, which some viewers found refreshing and others found inconsistent.

Why the cartoon ended in the USA - a brief note on Japan

The US run of the original Generation 1 cartoon ended for a handful of interconnected reasons:

Business/product cycle — The G1 toyline was built on a rapid wave-a-year product cadence. By 1987 many of the original moulds and play patterns had been exhausted; Hasbro and Takara were already looking forward to new product directions and fresh brand strategies rather than extending the same continuity indefinitely. The commercial imperative of rotating inventory and launching new SKUs undercut the logic of an open-ended TV run tied to a fixed roster of toys.

Creative exhaustion and audience dynamics — After several seasons, the serialised fiction and production demands (plus the movie experiment) had altered the show’s tone and the composition of its audience. The shock reaction to major narrative gambits (Optimus’s death and revival) demonstrated both fan attachment and the risks of radical editorial choices. Sustaining high-impact storytelling in a format whose primary purpose remained product promotion became increasingly difficult.

Production and cost factors — Animation production was globally distributed and the costs/complexities of maintaining a high-quality syndicated show were significant. Hasbro’s priorities and available budgets shifted with changing market conditions, and broadcasters’ appetite for the existing syndicated package changed over time. These operational realities made continuation less appealing.

Strategic pivot to other markets — While the US TV run wound down, Japanese partners chose to continue the Transformers story in a locally produced series (Headmasters, Super-God Masterforce, Victory, etc.) that better matched Japanese merchandising strategies and TV markets. In effect, the brand’s narrative continuity fractured: the US television era of G1 ended in 1987, while Japan produced sequels tailored to its own toy and TV ecosystem. I won’t detail the Japanese sequels, but it is important to note that the Transformers story did not genuinely stop in 1987 — it continued, transformed, and diversified in Japan.

Final perspective

Between 1984 and 1987, Transformers moved from a clever Japanese toy concept into a globally recognised brand through a tightly coordinated, multinational campaign of toy design (Takara; Tokyo), marketing and distribution (Hasbro; Pawtucket, Rhode Island), comic-book identity (Marvel; New York City), US television production (Sunbow/Marvel Productions; New York/Los Angeles) and overseas animation execution (Toei in Tokyo, AKOM in Seoul under Nelson Shin).

The public overwhelmingly embraced the toys and cartoon; sales peaked mid-decade, and the franchise’s ambition were stratospheric before the 1986 movie. Ultimately, the same forces that created growth — rapid product cycles, cross-media coordination, and heavy merchandising dependence — constrained the series’ narrative freedom and eventually contributed to the US TV run’s end. Yet the brand’s international life continued: Japan produced its own serialised continuations, and the toys and the mythos remained in play through new products, comics and on into later reboots.

The Transformers G1 cartoon is one of the most ambitious advertising projects ever undertaken. To create so many amazing characters with such a large mythos, all to sell some toys, seems like a crazy endeavour that I just cannot imagine could – or would – ever be carried out (especially with so much love and attention) here in the 21st century.

It was fun researching these two articles. I felt like I had to do these to ground myself – to take a step back and think about how I got here. From now on I will probably write shorter, more frivolous articles based around the cartoons and the characters. Thank you for reading!